Moorpark College Cabaret

Dramaturgical Analysis

THA M10A- Summer 2023

By Josh Mercer

“You mean – politics? But what has that to do with us?” are the naively motivic words of Sally Bowles, Cabaret’s central character, and the tragedy that follows is a chilling answer to Sally’s rhetorical question. Cabaret gives us a representative snapshot of a time in German history plagued by an antithesis between political unrest and cultural indifference. Through mimesis,[1] the play invites us to look back through the historical record, to uncover and contextualize the motivating forces behind Cabaret’s most central questions: who am I, what am I worth, and what do I believe? What exactly has politics to do with us?

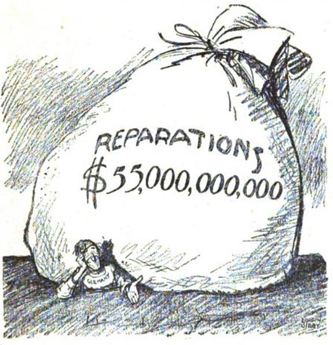

It is the dawn of the 1930s, and World War I has left the German economy reeling. The war was costly for all major powers involved, but for Germany in particular, military defeat blurred with economic defeat as post-war reparations made a painful dent in the German economy. The onset of The Great Depression at the tail-end of the 1920s only made matters worse. The result of this economic crisis in Germany was a severe hyperinflation of the Reichsmark, Germany’s currency. Rampant unemployment soon followed, and with it widespread panic as the working and middle classes saw their livelihoods endangered.

Germany's economy was in ruins just as much as was its national identity and pride after the war, and often it was difficult to tell the difference. Social unrest grew out of this age of maimed financial-political identity, and calls for a rehabilitation of Germany’s reputation on the national stage grew ever louder. Many Germans felt that the unideal resolutions that came out of World War I, outlined in the Treaty of Versailles, had been the fault of liberal leaders too willing to compromise and mutilate Germany’s pride. In the continuing economic collapse, this perceived complacency and ineffectuality of the current government only seemed to confirm itself. In response, right wing voices grew stronger, promising to remedy these national insults and reclaim the essence of Germanness itself.

It was out of this milieu of socio-political unrest that the Nazi party saw its opportunity to seize control. Originally formed as a worker’s union, the Nazi party played on Germans’ insecurities and desires in this time of instability by promising to reconstruct the German economy, rewrite the losses of the Treaty of Versailles, and prevent a Communist takeover. Adolph Hitler advanced to the proscenium of the world stage through his hypnotizing oratory prowess and the Nazis’ strategic propaganda. But the Nazis’ power and appeal were engendered by more than simply the sum total of their political objectives and promises; what the Nazis seemed to offer for many Germans was the opportunity to feel German once again.

To appeal to a wide audience in straightforward and easily manipulable terms, Hitler and his followers needed a universal and monolithic common enemy against which to unite. Especially in light of Germany’s economic collapse and wounded national pride, many people, whether consciously or unconsciously, were eager to place the blame somewhere; the Nazis pointed the national finger at the Jews. Antisemitism in Europe was nothing new. This painful history of racism extends back to classical antiquity. Throughout history, Jews have been depicted in certain populations as demonic and depraved, or as opponents to "moral Christian values." These antisemitic cultural tropes proliferated into the medieval era, when Jews were prohibited from owning land and holding most jobs. This caused many Jews to turn to trade and money lending to support themselves and their families, professions which fostered resentment towards Jews for their perceived control of finance. Given this history lurking in the recesses of the European zeitgeist, it is not surprising that the Nazis accused the Jewish people of responsibility for Germany’s economic collapse. The Jews, went the story, controlled the economy from behind closed doors, and now they had sabotaged it. In an extension of the pattern of equating economy with nation, Jews were also blamed for Germany’s defeat in World War I. In the eyes of the Nazis, the Jews had betrayed Germany on all counts and were unfit to live alongside the Aryan race.

But at the turn of the 1930s when Cabaret is set, the Nazi party had not yet risen to the degree of control and publicized hatred that defined the Holocaust. The Nazis had begun their climb to the top of the socio-political ladder, but they had done so largely in the shadows; they made up only 18% of Germany’s parliament in 1930. From a contemporary perspective, it is difficult to imagine a time when the word “Nazi” did not carry its now-intrinsic connotations of brutality, but this is precisely the task Cabaret demands we undertake; most Germans at the time, if they were aware of the Nazis, were not any more concerned with their presence as they would have been with any other political party. To be sure, the Nazis were growing steadily and were making plans for their horrific takeover; Hitler’s Mein Kampf had been out for several years. But they were still largely ignored or met with indifference. In Cabaret, multiple characters equate Nazis with Communists and Socialists in the same breath. Such statements speak to fundamental blind spots of the German people: that politics is never anything more than politics, and that the past can be expected to repeat itself in similar terms. Cabaret positions us in this retrospectively eerie state of liminal instability. Germany teeters in this historical nightmare between peaceful heterogeneity and the emergence of a nationalized, monolithic campaign for ethnic cleansing and world domination. The birth of one of history’s most shamefully acknowledged things of darkness is just beyond the horizon, but for now, many Germans, if asked about the prospect of Nazi political influence, would have echoed what Cabaret’s Fräulein Schneider says under analogous circumstances: “Who cares? So what?”

Cabaret also puts on display a peculiar social function of this period in Germany: the opposing poles of depersonalization and hyper-personalization of national conflict. The indifference that characters express towards politics and the Nazis is partially symptomatic of a cognitive separation of self from nation. Many Germans at the time did not feel that they had a strong personal link to the affairs of the nation and to its political state; in Cabaret, Fräulein Schneider protests that she herself is not at war with anyone, despite the growing tensions created by the Nazis. This depersonalization fosters indifference, willful ignorance, and dangerous complacency. It was these attitudes that allowed many Germans in this transitory period to remove themselves from the growing political fire and to pretend that inaction was not the same as supporting the Nazis’ dogma. On the other hand, nationalism and fascism, by their very definitions, involve a hyper-personalization of national conflict. Nazis and their sympathizers constructed the core of their public and private identities around national characteristics; their plight was the plight of Germany and of Germanness, an idea echoed by Cabaret’s Nazis: “our party will be the new builders of Germany.” The repulsion between these two forms of relating body to nation characterized pre-war and war-torn Germany, each paradoxically enabling the other.

For its exploration of German politics, Cabaret selects as its sample space a very specific subset of the greater historical context: the nightclub culture of the Weimar Republic. Cabaret’s Emcee and Kit Kat Klub are the contemporary representative relics of an explosion in art and performance in pre-war Berlin. The Kit Kat Klub is not a fictional invention; the real-life Klub was at the eye of the creative hurricane of this underground culture. This tradition of art was characterized by uninhibited sexuality and radical liberalism. Cabarets like the Kit Kat Klub performed raucous and bawdy music and comedy for their diverse, multinational audiences. These nightclubs became tourist attractions as well; Cabaret’s Emcee regularly waffles between languages to cater to his multilingual patrons. The cabaret culture was a testament to frivolous, empowered living; to go to the cabaret was to celebrate life on its surface–as Sally says, to “taste the wine,” to “hear the band,” and to “blow a horn, start celebrating.”

And yet, as much as Sally and other characters attempt to sever the cabaret and its culture from the politics of the day, the cabaret art form was fiercely political. Cabaret performances, under their external layers of sexual or moral provocation, regularly carried pointed political and social commentaries. The cabaret art form safely interrogated the culture of the day from the delegitimized perspectives of parody and vaudeville; this veil of medium both concealed and highlighted a meaning which was anything but disconnected from the public sphere. The rise of the nightclub culture of the Weimar Republic was concomitant[2] with the economic and political patterns discussed above; it moved and developed in formation with the other central cultural features leading up to World War II. This nightclub culture was then, in many ways, a mirror world to the greater, “real” society. The cabaret as a form was not an expression of secession from the political world, but rather a creation of its profoundly complementary underbelly. Thus, Sally Bowles’ safest, more blissfully carefree relic of her denialism is in fact an affirmation of what she does not want to believe: politics is inescapable.

And if Cabaret can be read as an extended answer to Sally’s question – “You mean – politics? But what has that to do with us?” – then this historicization brings out the full nuance of the musical’s verdict: everything. Politics has everything to do with us. It is in the money we spend, the way we gain it, the way we lose it. It is in our most fundamental morals which seem falsely inherent. It is in the entertainment we consume, however innocent and bipartisan it may appear to us to be. Politics lives in the dreams and desires that we house in our souls. Politics is the language through which we express want. It is the language of art, or else art is the language of politics. We speak through politics, and politics speaks through us. In the multilingual melting pot of 1930 Berlin, this is the one language that the characters of Cabaret cannot accommodate. As audiences of this piece in the modern day, we would do well to learn to read, write, speak, perform, breathe, exploit, and manipulate this language – otherwise it will manipulate us.